Increasing Access to Electricity and Reducing Emissions through Renewables

- CCAP

- Oct 25, 2012

- 4 min read

With rapidly growing demand for electricity, and with many citizens currently lacking access to electric supply, developing countries should consider policy options to economically deploy their substantial renewable energy potential. Various types of renewable energy can serve areas not connected to the power grid, provide more reliable water heating and meet base, intermediate and peaking electric demand. Renewable energy can displace new growth in fossil fuels, yielding important benefits to human health in sensitive populations while avoiding increases in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. For countries that import a considerable share of their energy resource, renewable energy can also support domestic energy security.

CCAP is currently working with countries throughout Asia and Latin America to develop opportunities for nationally appropriate mitigation actions (NAMAs) based on policy and financial support for major new growth in renewable energy. These actions will lead to reductions in GHG emissions as well as a better quality of life locally afforded by access to clean energy.

Latin America

Latin America is expected to see as much as a 75 percent increase in energy demand by 2030. Although this represents an enormous challenge, it also presents an opportunity for countries to capitalize on their abundant renewable resources, and by some estimates, renewable energy could account for up to half of the total demand.

Currently, Latin America and the Caribbean are global leaders in the exploitation of hydroelectricity and biofuel renewable energy resources, however it’s estimated that the region has only developed around 30 percent of its hydroelectric capacity, while the potential of new sources such as wind, solar and geothermal power have been left largely untapped. Although some countries in Latin America still lack renewable energy goals, others have adopted mandatory or voluntary targets that range from 8 percent by 2016 to 77 percent by 2030. Overall, most countries in the region could still benefit from additional policy and financial support to develop renewable energy resources and reap the associated environmental improvements, reductions in GHG emissions, increased fuel diversity and energy security, and economic development.

Asia

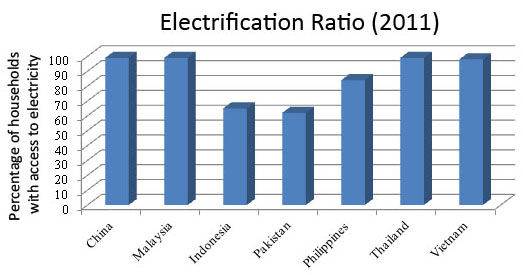

Growing populations, urbanization and industrialization are expected to lead to a near doubling of energy demand in the Asia-Pacific region by 2030, according to the Asian Development Bank. In particular, increasing energy production will be critical in meeting the needs of the approximately 700 million people in the region who currently lack access to electricity. In 2009, power generation in non-OECD Asia produced 4,781 Mt of CO2 emissions. Under a business-as-usual scenario, these emissions are expected to increase by over 140 percent to 11,600 Mt of CO2 by 2035

Asia has enormous potential for renewable energy deployment. For example, Indonesia and the Philippines have some of the world’s greatest geothermal resources, China and Pakistan have significant potential in wind and solar PV, and Vietnam has strong prospects for hydropower deployment. Yet despite this potential, only a fraction of Asia’s renewable resources have been developed. By harnessing this power through policies that target renewable energy, Asia can begin to bridge the gap and continue developing its economies.

Some of the primary renewable energy policy tools being used to spur development of renewable energy resources include:

Mandatory Renewable Energy Targets – Renewable portfolio standards (RPS) require electric utilities to meet an increasing share of electricity sales with renewable energy. Many such programs allow for trading of renewable energy credits as a way to enable a tougher standard and/or to achieve the standard at a lower cost. Another example of a mandatory renewable energy target is a standard requiring new buildings to supply a portion of their hot water with solar energy. While typically quite effective, the rationale and cost of mandates should be evaluated carefully alongside other options for meeting the desired policy objectives.

Financial Incentives – By covering a portion of the cost of renewable energy, financial incentives allow these resources to compete with conventional energy sources. Ideally such incentives would be needed only on an interim basis to help build local experience, increase economies of scale, and bring down costs. Feed-in tariffs have been widely used as a means of guaranteeing the price at which renewable energy producers can sell electricity. Other types of financial incentives include reverse auctions, tax incentives, loan guarantees, and sales or import tax exemptions. Financial incentives fit well into the NAMA construct where there is a clear role and rationale for international support.

Access-Oriented Policies – These include policies that provide fair terms to buy, sell and transmit power on the grid, policies that require electric companies to purchase renewable power or priority dispatch for renewable resources, and policies that enable renewable energy sources to bid for new transmission resources. These types of policies can help create a level (or preferential) playing field for renewable energy.

Education and Information – In some instances the government can collect and provide data on renewable energy potential, establish standards and certification procedures for renewable energy equipment, and conduct outreach and capacity building activities in the use of renewable technologies. The government can also help educate the utilities and banks that play a major role in renewable energy purchases.

As countries worldwide continue to consider mitigation actions involving renewables, CCAP will be showcasing recent success stories that have been particularly effective at deploying renewable energy, have done so at least cost, have effectively leveraged international support, or have effectively overcome barriers to deployment. The idea is that these success stories could be adapted to local conditions and developed as a NAMA, creating new opportunities for international support.

Comments